Our amazing person for today is a man who, due to his experiences that led to him not attending school for a few years, created the alter-ego robot, Orihime, to help erase loneliness from the world.

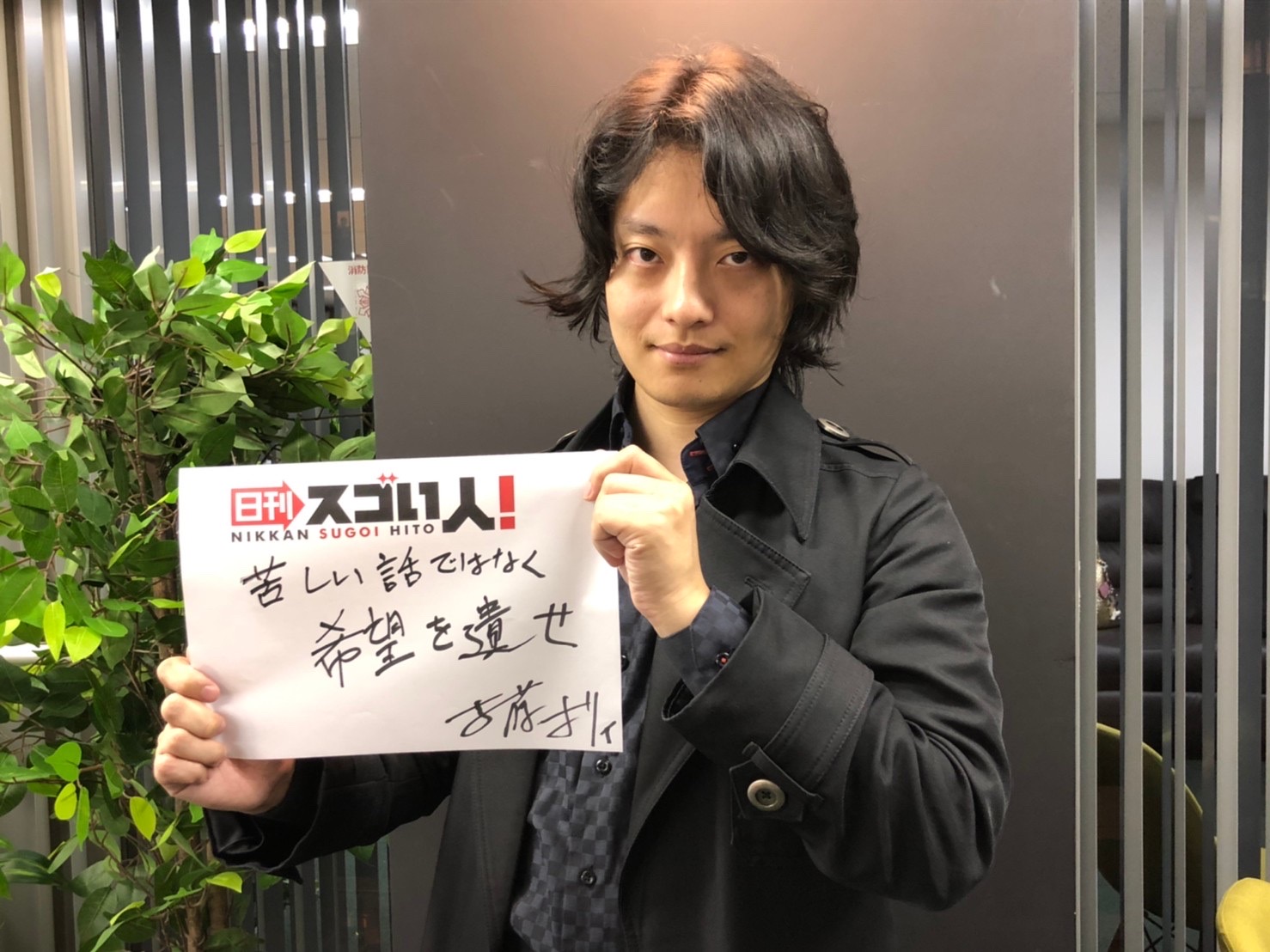

Mr Ori Yoshifuji, managing director, Ori research laboratory inc.

This week we would like to introduce the robot OriHime. It is a ray of light for those living in loneliness and isolation, and its creator continues to battle day and night to create a world free of these problems.

This an industry that didn't exist 20 years ago, where one finds themselves working day and night using robotics to find new ways for people that are unable to physically meet with people to form connections to society.

As someone who had experienced loneliness as a child, Mr Yoshifuji wished to send a ray of light to all the people still living in loneliness. In this article we hope to show our readers the amazing impact this grand idea has already had for many people.

Rather than song of hope than a bitter story

Day 1

The origin story. How four years of not attending school forged a desire to make things.

Interviewer (referred to as I from here): Thank you for coming to speak to us today.

Mr Yoshifuji (referred to as Y from here): No thank you, it is my pleasure.

I: It's been 4 years since we covered your story for the first time in 2016.Over these 4 years I expect the breadth of your activities has widened and that you have your eyes set on many more potential areas of growth?

Y: Yes, it's been quite a while hasn't it. I'm really glad for the increase of exposure over various forms of media (television, etc.), which has allowed us to spread information about Orihime and what another self robot is.

I: When we last spoke, you told us about how you didn't attend school for 4 years, from your 5th year of elementary school until your 2 year of middle school.

Do you still think that this experience had an immense impact on your life, or have your opinions regarding it changed?

Y: That's right, I still think that way. Learning origami from my grandparents allowed me to forget the loneliness I felt, and I spent many hours immersed in the activity improving myself .I was not good at school work or sports, so to have something that I could be better than others at allowed me to garner a degree of self-confidence.

I: Did you not do origami at school?

Y:I did, but what they called origami at school did not really feel the same to me. My origami is a creative art. Without following any particular design, I would fold the paper the way I felt was best.

In fact I'm not particularly good at what most people think of as origami. By that, I mean choosing some specific design, finding instructions in a book or manual, then following them to completion.

I: It seems like you were not good at working in a group.

Y: Yes, that's right. I found pre-planned work incredibly boring. During my 5th year at elementary school I spent around 15 hours a week creating my own origami. The results of this origami experience are without a doubt the origins of the creative work I now find myself undertaking today.

I: The person who helped you overcome this period of truancy was your mother if I remember correctly ?

Y: That's right. Because I was truant from school during this period, I would spend my days folding origami and playing games. However, one day all of a sudden my mother entered me into a robot contest. I had always been interested in robots so I took it as a challenge.

I: Did your mother suspect you of some special talent in robotics?

Y: Well you see, my mother had thought that a child who loves folding origami as much as I seemed to, must have a scientific mind, right?

Recently people have begun to think of origami as having a scientific/mathematical image to it, but when I was a child it did not have this sort of image at all.

So when I continued folding origami even though I had started elementary school, my parents became worried that there might be something wrong with me, it would be like someone in this day and age playing with a doll's house despite having already grown up.

It was the era when people would wonder why you weren't embarrassed to do such things.

It was in that era that my mother asked herself whether someone like me, who enjoyed making origami, might not also enjoy making a robot, and so entered me into the competition. This happened during my first year at middle-school.

I: It seems that you have always been interested in making things, though, doesn't it.

Y: Yes, I always have been. I've always loved silently making things by myself. Whether this was the cause or a result of it, I'm not sure, but I've always been bad at talking with people.

I could never really see the value in it. For me of that time, I would much rather have been making something, locked away in my own world.

I: So actually, through making robots, you began to develop a fascination with them?

Y: To be frank, I've never really thought about the appeal of making robots specifically. The fun of making something is physically speaking the same, and I've felt this fascination since I started making origami.

One part of the charm, is the fun bred from simple curiosity elicited by folding paper and seeing what shape comes out at the end. The other part of my enjoyment, was because at that time I was bad at studying and had no friends, so being able to fold origami was something I could do by myself and be recognised for. Being called amazing by people was a precious moment and such recognition was something I could only achieve through origami. So there is also this pragmatic side to my enjoyment.

This is of course a further reason for why I like origami.

Therefore, at the time there was nothing else about me that people respected besides my ability to make things, and as such it became something that I could take a bit of pride in.

Sue to this it was probably quite natural that I started making robots.

I: Despite that, to win a competition you must have had talent with robotics, right?

Y: This competition was to construct an off the shelf insect design robot, and program it as quickly as possible.

The other competitors seemed like the types of people that were good at studying at school, so if I tried to battle them at programming, I would have probably lost. Therefore, after a little thinking, I decided to try and move faster than them. It was possible to change the legs into different forms, but I left them in the original position. The other competitors spent time thinking about the best way to proceed, but I ploughed on using a trial and error method, and it brought success. In the end the others weren't able to do what they had set out to.

I: And you won.

Y: This victory allowed me to take part in a nationwide scale competition in Osaka, battling against the winners of the other smaller tournaments across the country. Unfortunately, I was only able to get second place this time. That day I learned the bitter difference between winning and coming in second place.

I: To put it simply, you were worried about people not respecting you, and this was the result of it?

Y: For the me of that time, building things was my only real form of communication.

I didn't attend school, and no-one really understood me. It was psychologically painful.

Many times I was burdened with thoughts like, “it would be better if I wasn't here.

No-one needs me, so maybe it's better if I somehow disappeared.” I tried to think of ways I could get people to like me. When I opened my eyes, I was standing in front of a lake, and I thought, “ah, my body wants to die.” I tried desperately to find a reason not to die.

At that time I had a moment of clarity and realised from the bottom of my heart that if I could make people happy by making things like origami or balloons, then it would be a life worth living.

In this way making things became my way of connecting with society, and a valuable tool for communicating.

I: By being praised by others, the value of your existence was confirmed.

Y: Yes, that's exactly right. I have a personal theory, I call it “the cost of praise”.

There are people who, without hesitation, go and help the people who seem in trouble. They may ask “is something the matter,” or are attentive and tell you “I've done it, don't worry”. The compensation cost of praise for these people is low.

Those are the people that are popular and always seem to have something interesting to say in class.

I: So it's the amount of time taken until they receive praise right.

Y: I also like drawing, you know. However, if I just draw any old picture, no-one is going to say “amazing”. If you make a picture or complicated model at the level that people would say “amazing”, the first time they see it they will say “amazing”, but the next time they'll say “you make a lot of this stuff right”, they won't say anything more.However, because you want to hear those words; hear that person once again say, “amazing”, you have to make something of a higher level.

It feels like this is the sole means of getting social approval and validation.

As evidence of this, a television program in the format of an origami competition started, and my eyes were opened to the fact that there were amazing people who were better at origami than I was.

I learned the cruel truth that, even though all I had in my life was origami there were many people to whom I was like dust under foot appeared before me.

And with that I quit making origami.

There was also a time when I became interested in balloon art, and made an interesting discovery.

Balloon art has a great cost of praise.

I: The Cost of praise is high?

Y: That's right. Origami is a world where you spend a long time, sitting quietly making precise fold after precise fold, all to hear the word amazing. Balloon art, however, is another process that can be used to hear the word “amazing”.

Children excitedly watch as the as the balloon artist pumps air into the balloons, making them swell and change shape. As the balloons are twisted into different forms they let out squeaking noises, and it takes barely a minute.

Rather than slaving away like a dog for hours, spending just 20 seconds shaping the balloon in front of the child brings joy to their eyes.

Rather than for performing an amazing task, this “amazing” is... what's the best way to put it, rather than a reward for your hard efforts, a large portion is for the simple entertainment that it brings to people. To a creator specialising in making things, this appears absurd.

Here was a lesson for me, despite working hard my efforts had not been recognised, but there are things you don't have to work hard at to receive praise (laughs).

(Continue tomorrow)

Editors:ALLES・NORIKO・TIM WENDLAND